Special Chapter for Lust, Lies and Monarchy

Black lives matter!

In 1848, the king’s army attacked a large village called Okeadan, located in what today is Nigeria. It was a brutal assault, with hundreds of residents decapitated and tortured to death. The rest were marched away into captivity.

Among the captives was a young girl, only about five years old. The scars on her face indicated she was of noble birth, and she was moved to the capital of Dahomey. Most of the other captives were sold into slavery. The young girl had witnessed the execution of both her parents, and her siblings had disappeared. She was completely alone.

The young girl was kept for two years in a small room. From time to time, other captives were dressed in white and bound. They were then put in baskets and taken out to be sacrificed in front of the king, being beaten and stabbed before their heads were cut off. The sprinkling of their blood on the graves of the tribe’s ancestors was a long-practised tradition.

It is almost impossible to imagine how traumatised the young girl must have been, knowing her turn to be sacrificed could happen at any time. Nearly all her childhood memories would have been terrible ones.

However, the girl’s life was about to change dramatically. In 1850, a 30-year-old British naval officer named Captain Frederick Forbes arrived on a mission to persuade the king of Dahomey to stop his trade in slaves. Forbes was a tough, brave man, who a few months before had led his ship, H.M.S. Bonetta, during the capture of six slave ships off the African coast. However, venturing into the territory of a feared ruler such as Gezo must have been a daunting challenge.

Forbes managed to survive his dangerous mission to the king, although Gezo refused to stop his slave trade. As was customary, as Forbes was preparing to leave the king, there was a diplomatic exchange of presents. Forbes would later recall the king offered “a rich country cloth, a captive girl, a cabooceer’s stool, a footstool…”

The “captive girl” was the little girl of royal blood who had survived the attack on her village and two years in captivity. Gezo described the girl as a present for Queen Victoria. Forbes later wrote: “One of the captives of this dreadful slave-hunt was this interesting girl. It is usual to reserve the best born for the high behests of royalty and the immolation on the tombs of the deceased nobility…”

Forges realised he could not refuse the gift of a human being as to do otherwise “would have been to have signed her death-warrant, which probably would have been carried into execution forthwith.” However, it must have been a strange acquaintance—a tough naval officer thousands of miles from home and a young African girl who could speak no English and knew nothing of her new ‘owner’s’ world.

Forbes hurried back to his ship and gave the girl a name—Sarah. The rest of her name was derived from his own surname and the name of his ship. Sarah Forbes Bonetta was now placed on Forbes’ ship as it began its long journey back to England.

It would be the first of many voyages Sarah would undertake in her life. This must have been a lonely one, with only white, male sailors to mix with, and no idea of what sort of life lay ahead of her. But Sarah quickly began to show the resourcefulness that had helped her survive adversity for so long, and by the time she reached England she could already speak English.

The next shock for Sarah was arriving in England. The climate was cold, and society was completely different to what she had known all her life. She was also a black African child in the heart of an empire controlled largely by white people, and in which prejudice against other racial groups was commonplace.

Captain Forbes felt obliged to write to his superiors informing them he had been entrusted with a diplomatic present—Sarah—for Queen Victoria. Forbes had a wife and children of his own, and planned to bring up Sarah himself. However, the Queen learnt of Sarah’s incredible story and decided to bring the young girl under her wing. Forbes would recall how he was astonished to be informed “Her Majesty was graciously pleased to arrange for the education and subsequent fate of the child.”

In November 1850, the Queen asked for Sarah to visit her at Windsor Castle, one newspaper account describing the girl “as a present to our Queen from the King of Dahomey.” Sarah also met Prince Albert and six of their children, another newspaper describing how “the little girl was mostly kindly shaken by the hand by Her Majesty and the Royal Children, and went through the interview with great self-command.”

Queen Victoria kept a detailed diary for most of her life, and on 9 November 1850 wrote:

When we came home, found Albert still there, waiting for Capt: Forbes & a poor little Negro, girl, whom he brought back from the King of Dahomé, her Parents & all her relatives having been sacrificed. Capt: Forbes saved her life, by asking for her as a present. She was brought into the Corridor. She is 7 years old, sharp & intelligent, & speaks English.

Sarah charmed anyone who came into contact with her, and the queen regarded her as an African princess who should be supported and treated with kindness. The queen used her nickname ‘Sally’ and paid for her education. Sarah turned out to be a good student, and Forbes described her as a “perfect genius; she now speaks English well, and has a great talent for music…She is far in advance of any white child of her age in aptness of learning.”

In 1851, the queen commissioned a painting of Sarah from Octavius Oakley. It would be the last time Sarah was depicted in her traditional dress; from now on she was dressed, educated and learnt the manners of an upper-class Victorian child.

The first meeting with Victoria was just the beginning of a close connection between Sarah and her descendants with the British royal family. For example, in January 1851 the Queen would write:

After luncheon Sally Bonita, the little African girl came with Mrs Phipps, & showed me some of her work. This is the 4th time I have seen the poor child, who is really an intelligent little thing.

However, just as Sarah was settling into her new life in England, a new tragedy would strike. Captain Forbes, the kindly man who had saved her from certain death, died whilst at sea. Mrs Forbes, now a widow with several of her own children, was unable to look after Sarah as originally planned. Sarah’s health was also suffering in the cold climate.

Victoria decided it would be best for Sarah to be sent to a missionary school in Sierra Leone. Once again Sarah was on a ship, this time going back to Africa—separated from the people she had begun to forge a connection with in England.

Everyone at the school knew she was Victoria’s protégé, and she excelled at her lessons. However, for some reason, she was never truly happy there, and she persuaded Victoria to let her return to England when she was 12.

Upon her return, she was placed with a missionary couple whom she grew very fond of and treated as if they were adopted parents. Sarah also continued to visit the royal family at Windsor and St James’s Palace, even attending the wedding of one of Victoria’s daughters.

As she entered her late teens, Sarah was aware that despite her royal connections, she was nevertheless a young black woman in Victorian England who was wholly dependent on the patronage of others to survive. When Victoria applied pressure on Sarah to marry an African merchant and former slave named James Pinson Labulo Davies, Sarah tried hard to resist. He was a widower and in his thirties, and Sarah was not attracted to him; but when it became clear she had little choice, she eventually gave in.

In 1862, a British newspaper reported on an “Interesting Marriage at Brighton.” According to the article, “a marriage was performed at the Parish church, Brighton, to unite a lady and gentlemen of colour.” As Sarah entered the church she was described as nervous. It was also reported that “Her Majesty…has taken a great interest in her marriage,” and the ceremony was performed by the Bishop of Sierra Leone. Unusually for mid-19th-century England, the wedding guests were a multiracial crowd, and press reporters seemed almost unsure of what to make of such an occurrence.

Despite her concerns about her husband, for the first time in Sarah’s life she had some control over her own life. She moved with him to begin a new life in Sierra Leone, still keeping in contact with Victoria and visiting the royal family whenever she came back to England.

Sarah would become a teacher and have several children. She sought the queen’s permission to call her first daughter Victoria, and the queen agreed, also becoming the child’s godmother.

On 9 Dec 1867, the Queen would write in her diary:

After luncheon saw Sally, now Mrs Davis, & her dear little child, far blacker than herself, called Victoria & age 4, a lively intelligent child, with big melancholy eyes.

Having survived such difficulties so far in her life, by any right Sarah deserved some good luck now she was married and had children. However, the cough that had plagued her since she was a child came back with a vengeance, and she was diagnosed with consumption.

Her husband sent her to the island of Madeira, hoping the good climate there would help her recover, but she was dying.

On 23 August 1880, Victoria wrote:

Grieved & shocked to hear, that poor Sally, (Sally Bonetta Forbes) Mrs Davies, was hopelessly ill at Madeira. — Ly Dudley brought her 4 eldest children, for me to see, 3 fine, nice boys, & a very pretty little girl.

Sarah died that same year. She was only 37 years old, and the monument erected by her husband refers to Princess Sarah Forbes Bonetta.

Upon Sarah’s death, the Queen wrote in her diary:

Saw poor Victoria Davies, my black godchild, who learnt this morning of the death of her dear mother at Madeira. The poor child was dreadfully upset & distressed, & only got the news as she was starting to come here..Victoria seems a nice girl….I shall give her an annuity.

Whilst Sarah died tragically young, her legacy was her children and today many descendants in Sierra Leone, England and Nigeria can trace themselves back to the young girl who was so nearly sacrificed by the king of Dahomey.

Even after Sarah died, her children and grandchildren kept in contact with Queen Victoria. In November 1900, just a few months before she died, the queen met her godchild Victoria Davies (now married and called Victoria Randle). She came to Windsor Castle with her own two children, the same place their grandmother first met the queen half a century before.It was no doubt a poignant meeting, and the queen must have thought about how her own life had changed since she first met Sarah. The connection with the royal family was not just limited to the queen herself. One of Victoria Randle’s children was named Beatrice, after the queen’s daughter Princess Beatrice, and the princess acted as the girl’s godmother.

A newspaper report described a “homely and touching little scene” in which the queen “granted the children the favour of kissing her hand, whilst she herself kissed them and their mother also, and gave some nice presents to the little ones… the story of the Queen’s connection with this West African family goes back and a long way.”

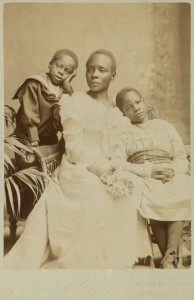

Touchingly the Royal Collection contains a photograph of Sarah’s daughter Victoria Randle and her children dating from 1901.

For more fascinating stories about UK royal families, check out Lust, Lies and Monarchy: The Secrets behind Britain’s Royal Portraits by Stephen Millar! This volume is sumptuously illustrated, includes family trees and a timeline, and features four Royal London Walking Tours with maps.

Add to Cart

Although the chapter on Sarah Forbes Bonetta was dropped from the published book, click to get fascinating royal stories from Stephen Millar’s Lust, Lies and Monarchy.

MUSEYON BOOKS Smart City Guides for Travel, History, Art and Film Lovers

MUSEYON BOOKS Smart City Guides for Travel, History, Art and Film Lovers